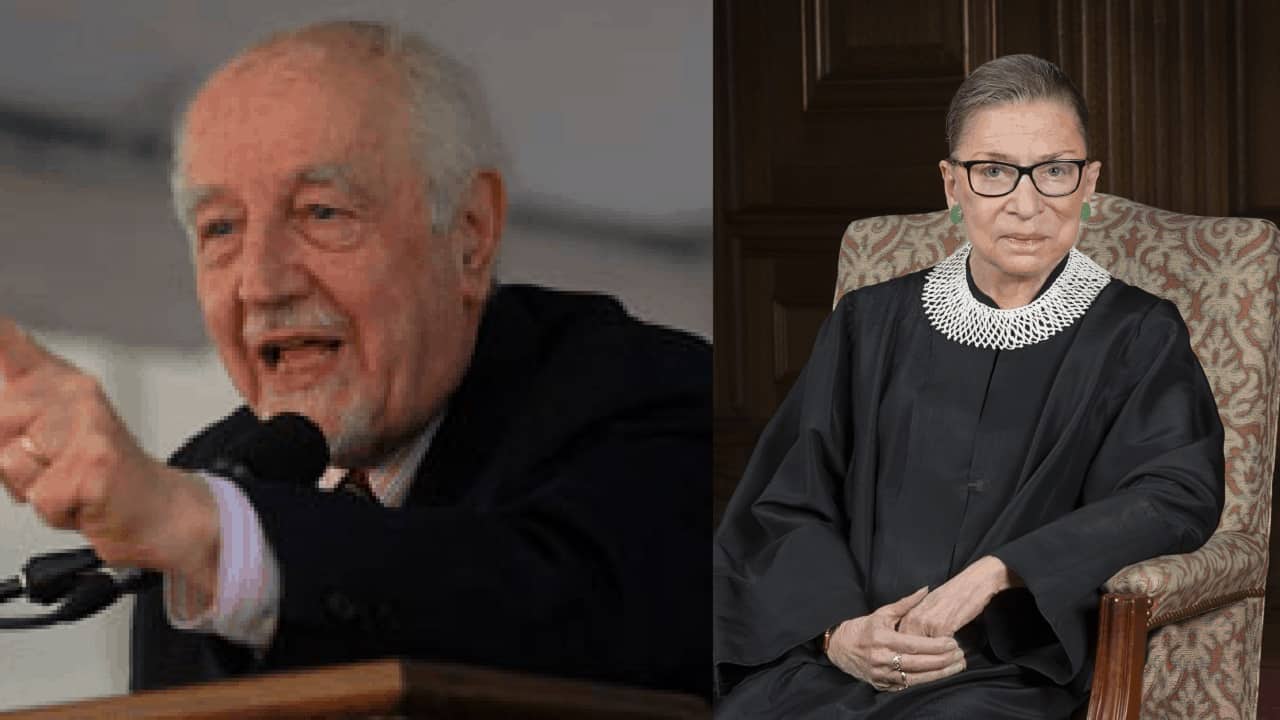

Remembering Ruth Bader Ginsburg*

di Guido Calabresi

*traduzione a cura di Gery Ferrara

Guido Calabresi ci regala un ricordo personale di Ruth Bader Ginsburg (aggiungere anche una sola parola nuocerebbe allo straordinario peso della sua memoria), dopo che nei mesi scorsi ha offerto il suo impulso decisivo ad alcuni approfondimenti sui temi delle scelte tragiche nel tempo del Covid - Tragic choices, 42 anni dopo. Philip Bobbitt riflette sulla pandemia - e della condizione degli afroamericani negli USA -Le lacerazioni razziali negli Stati Uniti: la comprensione del fenomeno di Tom Tyler (Yale University) -. In questo si coglie il Suo desiderio di tenersi unito alla sua terra d'origine e che abbia scelto i lettori di Giustizia Insieme per mantenere il legame ci onora.

Tutto questo non sarebbe stato possibile senza Gery Ferrara che ringraziamo con grande stima.

Guido Calabresi gives us a personal remembrance of Ruth Bader Ginsburg (adding even a single word would harm the extraordinary weight of his memory) after he offered us, in the last months, his decisive input in deepening on the subject of tragic choices over covid-time - Tragic choices, 42 anni dopo. Philip Bobbitt riflette sulla pandemia – and on the conditions of African Americans in the USA - Le lacerazioni razziali negli Stati Uniti: la comprensione del fenomeno di Tom Tyler (Yale University) -. In this, we figure out his desire to be close to his homeland and the choose and we are honored he has chosen Giustizia Insieme readers to maintain this link.

All of this would not be possible without Gery Ferrara whom we thank with great esteem.

***

Ruth Bader Ginsburg era mia amica. Avevamo quasi la stessa età. E siamo diventati giudici nello stesso periodo, lei alla Corte Suprema degli Stati Uniti e io alla Corte d'Appello degli Stati Uniti. Entrambi abbiamo iniziato la nostra carriera nel mondo accademico. E nei nostri scritti abbiamo espresso opinioni simili su molte delle questioni chiave del momento. Ad esempio, siamo stati entrambi critici nei confronti del ragionamento giuridico alla base della sentenza Roe v. Wade (il caso che ha stabilito il diritto costituzionale di una donna all'aborto) senza, per questo, essere in disaccordo rispetto alla decisione finale.

È interessante notare che quella posizione aveva originariamente fatto sorgere delle preoccupazioni, soprattutto in certi ambienti di sinistra, sul tipo di giudici che saremmo stati. Tuttavia, il presidente Clinton era determinato a nominarci entrambi. Ed entrambi siamo stati confermati dal Senato praticamente all'unanimità. Durante il suo periodo in Corte, più di una volta R.B.G. ha citato favorevolmente decisioni del mio tribunale, seppure di grado inferiore, e ha citato il ragionamento da me seguito nelle sue opinioni. E spesso ha assunto i miei assistenti quando questi avevano finito il loro periodo presso il mio ufficio, per farli diventare suoi assistenti. Non dovrebbe, dunque, sorprendere che io scriva di lei con grande affetto e senta profondamente la sua perdita.

Ma c'erano anche delle differenze importanti tra noi, specialmente nel modo in cui ognuno di noi ha reagito alle discriminazioni di fondo che hanno fatto parte della storia dell'America, tanto quanto o forse in misura maggiore che in altri paesi.

Quando eravamo giovani, siamo stati entrambi oggetto di discriminazione da parte di alcuni, ma siamo stati anche fortemente aiutati da parte di altri; lei molto più di me è stata ostacolata da maggiori pregiudizi. Io ho reagito ai pregiudizi nei miei scritti accademici; lei diventando un grande avvocato dedito alla causa dell'uguaglianza.

E che avvocato era. Seguendo il modello di Thurgood Marshall, e di coloro che avevano guidato la lotta contro la segregazione razziale, ha costruito, caso per caso, la struttura che nel tempo avrebbe abbattuto la maggior parte delle discriminazioni legali contro le donne.

Eppure, ed e questa è la sua grandezza, lei non si è fermata a questo, perché l'uguaglianza e la dignità di ogni essere umano erano il fulcro del suo credo.

E così, mentre iniziava a combattere per il riconoscimento della dignità delle donne, ampliava la sua lotta a tutela degli uomini, a coloro il cui orientamento sessuale era diverso dal suo, alle persone di colore - agli studenti bisognosi di una educazione speciale - ai detenuti - agli immigrati e ai rifugiati - e ai poveri.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg era tradizionale, si potrebbe dire conservatrice, nella sua vita personale. Era immensamente devota a suo marito, ai suoi figli e ai suoi nipoti, i quali la adoravano. Sembrava una radicale solo perché combatteva per la giustizia - per le persone e non per il potere. E per questo motivo, questa minuscola, piccola e fragile persona ha finito per sembrare enorme.

Il Vangelo della domenica successiva alla sua morte raccontava dei lavoratori che arrivavano alla vigna presto o tardi durante la giornata. Ruth è arrivata presto alla vigna e si è guadagnata abbondantemente la sua paga. Ma ha accolto con gioia anche tutti coloro che sono arrivati in ritardo.

***

Ruth Bader Ginsburg was my friend. We were nearly the same age. And we became judges at about the same time, she on the Supreme Court of the United States and I on the United States Court of Appeals. We both began our careers in the academy. And in our writings, we expressed similar views on many of the key issues of the day. For example, we both were critical of the reasoning in Roe v. Wade (the case that established a woman’s constitutional right to an abortion) without, for that, disagreeing with the result. Interestingly, that position originally led to concern among some of those on the left as to the kind of judges we would be. Nevertheless, President Clinton was determined to appoint each of us. And we were each confirmed by the Senate virtually unanimously. On the Court she, more than once cited favorably my lower court opinions and my reasoning in her own opinions. And she frequently hired my law clerks when they had finished their time with me, to become law clerks with her. It should be no surprise that I write of her with great affection and feel her loss profoundly.

But there were also important differences, and especially in how we each reacted to the underlying discriminations that have been a part of America, as much or more as of other countries. When we were young, we both were the objects of discrimination by some, and of great help from others; she much more than I was hampered by greater biases. I reacted to bias by scholarly writings; she by becoming a great lawyer dedicated to the cause of equality. And what a lawyer she was. Following the model of Thurgood Marshall, and of those that had led the fight against racial segregation, she built, case by case, the structure that would in time bring down most legal discriminations against women.

Yet, and this is her greatness, she did not stop there, for equality and human dignity of every human being framed the core of her belief. And so while she began fighting for the recognition of the dignity of women, she expanded this to men, to those whose sexual orientation was different from hers to people of color – to students in special education – to prisoners – to immigrants and refugees – and to the poor.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg was traditional, conservative one might say, in her personal life. She was immensely devoted to her husband, her children, and her grandchildren, all of whom adored her. She seemed like a radical only because she fought for justice – for people not for power. And for this reason, this tiny, tiny frail person came to seem enormous. The gospel of the Sunday after she died told of workers coming to the vineyard early and late in the day. Ruth came to the vineyard early and earned her pay mightily. But she happily welcomed all those who came late.

And then Add to Home Screen.

And then Add to Home Screen.